This page explains my PhD reserach project and related ATES smart Grids project.

(for Dutch scroll down)

ATES Smart Grids research program overview and summary

Nice Dutch article explaining the basics of our research: Onderzoeksproject_URSES_Keviczky

Summary of paper on ATES planning on sciencetrends.com

ATES

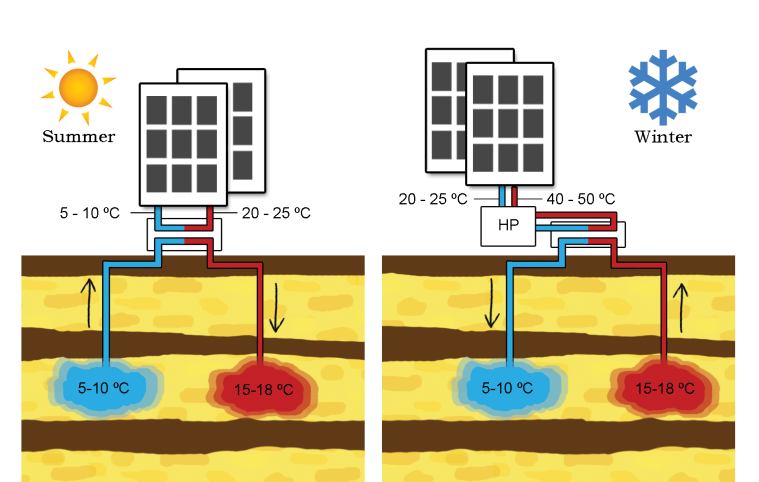

Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage (ATES) systems contribute to reducing fossil energy consumption by seasonally storing heat in underground aquifers. Combined with a heat pump, these systems can provide more sustainable heating and cooling for buildings, and they can reduce the use of energy in bigger buildings by more than half. ATES is therefore important for the energy transition in many urban areas in North America, Europe and Asia. In the Netherlands, where shallow aquifers make the technology especially cost-effective, ATES is currently used in around 10% of new buildings; while this market share is still modest, the demand of subsurface space for ATES has already grown to congestion levels in many Dutch urban areas.

Problem: suboptimal use of the subsurface as energy storage

The deep subsurface plays a crucial role in the energy saving objectives of The Netherlands when considering the heating and cooling of buildings [1,2]. The vision of TU Delft is that the enormous potential of this sustainable energy source must be utilised in a stable and optimal fashion. However, given the current state of technology and operating within the exisiting legal framework, this is not guaranteed [3].

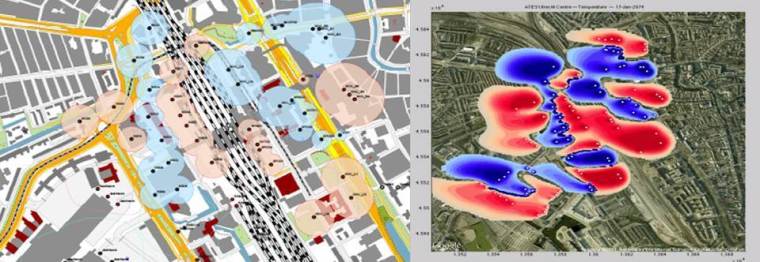

Experience with existing system installations suggests that the current approach to the design, planning, and predetermination of operating limits via permits and master plans, do not deliver the desired results with respect to the optimal and sustainable use of the subsurface [3,4]. The most significant problem is the permanent (and often unused [3]) claims that the permits form over available subsurface space. This creates difficulties for potential new users and limits the application and adoption of ground energy storage solutions. Recent research has shown that ground energy storage systems could be placed much closer to each other [5,6], and a controlled/limited degree of interaction between them can actually benefit the overall energy savings of an entire area. An excessive spatial restriction thus leads to unnecessary artificial shortages of underground space. In addition, due to the lack of monitoring it is not known what really happens to energy stored underground. In crowded urban areas where subsurface energy systems are situated close to each other, unwanted and/or unexpected effects can arise due to hydrological and thermal interference as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1, Thermal interference between ATES systems near Utrecht central station,

Left: master plan based on analytical calculations, Right: groundwater model simulation of 75 years of operation

Solution: the approach and first results of our research project on ATES Smart Grids

The cooling and heating of buildings is a dynamic and on both short and long terms hard to predict process, due to effects such as weather, climate change, changing function and usage of buildings over time. This applies then naturally to ground energy storage use as well. It is therefore logical to shift the regulation from the planning phase to the operational phase. The spatial distribution and performance of these systems can only be adjusted and influenced in the operating phase, where the energy savings are also realized and the climate control targets are achieved as well.

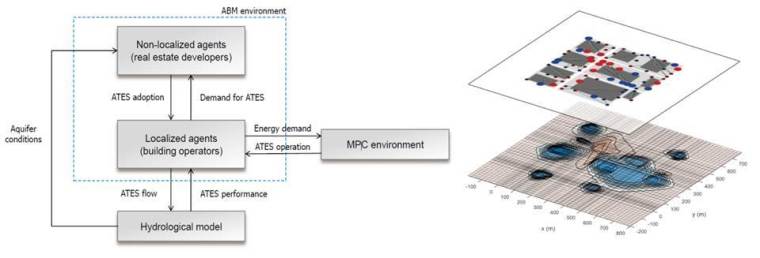

The subsurface is a common pool resource [7] and geothermal energy systems actually meet the requirements for successful application of self-organization principles [3,8,9]. Our solution therefore provides a framework in which exchange of information is central to deciding on the application and use of geothermal energy based on the current state of the subsurface. With this information, current and future users can adjust their own operation based on the actual subsurface, via a controller and compensation measures. In order to arrive at a proof-of-concept based on our approach, we use expertise and models from different fields such as administrative policy and decision making, systems and control, and hydrogeology. Figure 2 illustrates schematically how the various models interact with each other.

Figure 2, Modeling framework for ATES Smart Grids, Left: conceptual design, Right: visual representation of ABM and hydrological model layers

A central element is the so-called agent-based model (ABM). Each ATES system is an agent that can function autonomously based on a specified set of rules. Agent-based modeling is a technique widely used in administrative policy and decision making in order to simulate the behavior of actors. Each agent has a controller that determines how the geothermal energy system must satisfy the energy demand of the building, thus the properties and characteristics of the building and the system are included in the controller. We apply a so-called Model Predictive Control (MPC) approach, which means that the controller is looking ahead and takes into account the expected energy demand in the future, and also how its control strategy influences the performance of its own resources. The computed control action is implemented on a groundwater model of the area including all geothermal energy systems, which then serves as the basis for planning the control actions over the next period.

This concept is developed in 3 steps up to the scale of a typical Dutch town. Currently we have a proof-of-concept based on a fictitious academic model, which we will scale up to the center area of Utrecht and then the entire city of Amsterdam.

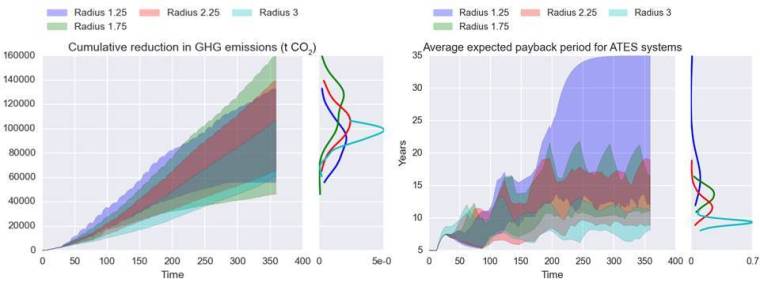

The first results using the academic model are promising [10]. Figure 3 shows that stable situations result even for geothermal energy system that are placed a lot closer together than what current regulations would dictate. This has a positive effect on the total CO2 emission reduction, but a negative effect on individual efficiency.

Figure 3, Results of the academic “sandbox” model, the effect of different distances between the sources (as a function of the thermal radius) on total emission reduction (left) and efficiency of individual systems (right)

Conclusions

The subsurface is a valuable energy source/storage that should be handled carefully in terms of policy and technical solutions. Only by incorporating the whole subsurface in the operational management of geothermal energy systems can we guarantee the preservation of this storage function. The first results of a framework in which ATES systems exchange information and self-regulate the use of the subsurface are very promising, and it will be further developed on the basis of case studies and further improvements to the models and controllers.

References

[1] SER, “Energie Akkoord,” Sociaal Economische Raad, 2013.

[2] Kamerbrief Warmtevisie, Correspondentie van Zijne Excellentie Minister Kamp naar de 2de kamer der Staten Generaal de Nederlanden, 2 April 2015

[3] M. Bloemendal, T. Olsthoorn, and F. Boons, “How to achieve optimal and sustainable use of the subsurface for Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage,” Energy Policy, vol. 66, pp. 104–114, Mar. 2014.

[4] Q. Li, “Optimal use of the subsurface for ATES systems in busy areas,” MSc thesis, Delft University of Technology, 2014.

[5] W. Sommer, J. Valstar, I. Leusbrock, T. Grotenhuis, and H. Rijnaarts, “Optimization and spatial pattern of large-scale aquifer thermal energy storage,” Appl. Energy, vol. 137, no. 2015, pp. 322–337, 2015.

[6] M. Bakr, N. van Oostrom, and W. Sommer, “Efficiency of and interference among multiple Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage systems; A Dutch case study,” Renew. Energy, vol. 60, pp. 53–62, Dec. 2013.

[7] G. Hardin, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” Science, vol. 162, no. 3859, pp. 1243–1248, Dec. 1968

[8] E. Ostrom, 2009. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science, 235, 419-422.

[9] R. Caljé, 2010. Future use of aquifer thermal energy storage inbelow the historic centre of Amsterdam. MSc-thesis. Delft: Delft University of Technology,

[10] M. Jaxa-Rozen, J.H. Kwakkel, M. Bloemendal, The adoption and diffusion of common-pool resource-dependent technologies: the case of Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage systems, paper for the 2015 Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering and Technology (PICMET), August 2-6, 2015

## DUTCH

Onderzoeksprogramma “Bodemenergie Smart Grids”

Probleem: suboptimaal gebruik van de bodem met bodemenergie

De ondergrond speelt voor het koelen en verwarmen van gebouwen een cruciale rol bij de energiebesparing die Nederland voor ogen staat [1,2]. De visie van de TUDelft is dat de enorme potentie van deze duurzame bron van energie bestendig en optimaal moet worden benut. Met de huidige stand der techniek en binnen de huidige praktijk en wettelijke kaders is dit echter niet gewaarborgd [3].

De ervaring met bestaande systemen leert dat de huidige aanpak met ontwerpen, plannen en inpassen vooraf, via vergunningen en masterplannen, niet het gewenste resultaat oplevert ten aanzien van optimaal een duurzaam gebruik van de bodem [3,4]. Het belangrijkste probleem is de permanente en grotendeels ongebruikte [3] claim die de vergunningen leggen op de ondergrondse ruimte. Dat frustreert nieuwe initiatiefnemers en beperkt de toepassing van bodemenergie. Recent onderzoek heeft aangetoond dat bodemenergiesystemen dichterbij elkaar kunnen worden geplaatst [5,6], een gecontroleerde/beperkte mate van interactie komt de overall besparing van energie in een gebied ten goede. De overmatige ruimtelijke restrictie zorgt dus onnodig voor kunstmatige schaarste van ondergrondse ruimte. Daarnaast is het door gebrek aan monitoring onbekend wat er met ondergronds opgeslagen energie gebeurt. In drukke stedelijke gebieden waar de bodemenergiesystemen dicht bij elkaar staan kan de onderlinge hydrologisch en thermisch beïnvloeding voor ongewenste en/of onverwachte effecten zorgen, figuur 1.

Oplossing: Onderzoeksprogramma Bodemenergie Smart Grids; aanpak en eerste resultaten

Het koelen en verwarmen van gebouwen is door het weer, veranderend klimaat, veranderende functie en gebruik van een gebouw een zowel op de korte als op de lange termijn moeilijk te voorspellen proces. Het gebruik van de bodem van de bodemenergiesystemen van die gebouwen daarmee ook. Daarom is het logischer om de regie van planningsfase naar de operationele fase te verleggen. Alleen in de bedrijfsfase kan er worden bijgestuurd en kan er invloed op de ruimtelijke verspreiding en prestaties van de systemen worden uitgeoefend, in de operationele fase worden de besparingen gerealiseerd en de klimaatdoelstellingen behaald.

De bodem is een common pool resource [7] en bodemenergie systemen voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor succesvolle toepassing van zelf organisatie [3,8,9]. Onze oplossing voorziet daarom in een raamwerk waarin uitwisseling van informatie centraal staat om de actuele toestand van de ondergrond te gebruiken bij beslissingen over toepassing en gebruik van bodemenergie. Met deze informatie kunnen de huidige en toekomstige gebruikers op basis van het daadwerkelijke bodemgebruik hun eigen gebruik aanpassen, via een controller en compensatie maatregelen. Om tot een proof of concept te komen van deze aanpak gebruiken wij expertise en modellen uit verschillende vakgebieden; bestuurskunde, systems & control, geohydrologie. In figuur 2 is schematisch weergegeven hoe de verschillende modellen met elkaar interacteren.

Centraal staat het zgn agent-based-model (ABM). Elk bodemenergiesysteem is een agent en die kan op basis van een opgegeven set van gedragsregels autonoom functioneren, agent based modeling is een veel gebruikte techniek in de bestuurskunde om gedrag van actoren te simuleren. Elke agent heeft een controller die voor de agent bepaald hoe het bodemenergie systeem aan de energie vraag van het gebouw moet voldoen, gebouw en systeem eigenschappen zitten dus in de controller. Het voldoen aan de energievraag en het optimaliseren van het ondergrondse ruimte gebruik gebeurd vervolgens met “model-predictive-control” (MPC). Dit betekent dat de controller vooruit kijkt en rekening houdt met energie vraag in de toekomst, en in dit geval ook hoe zijn control strategie het rendement van zijn eigen bronnen beïnvloedt. De uiteindelijke uitgevoerde control-actie wordt gemodelleerd met een grondwater model van het gebied met alle bodemenergie systemen, op basis waarvan het gebruik voor de volgende periode weer wordt vastgesteld.

Dit concept wordt in 3 stappen uitgewerkt en verbeterd naar de schaal van een Nederlandse stad. Momenteel hebben we een proof-of-concept op basis van een fictief academisch model, wat we gaan opschalen naar het centrum gebied van Utrecht en vervolgens heel Amsterdam.

De eerste resultaten van het academische model zijn veel belovend [10]. Figuur 3 laat zien dat er stabiele situaties ontstaan voor bodemenergie systeem die een stuk dichterbij elkaar staan dan momenteel in de regelgeving wordt gehanteerd. Dit heeft een positief effect op de totale CO2 uitstoot reductie, maar negatief effect op individuele efficiëntie.

Conclusie

De bodem is een waardevolle buffer/bron van energie waarmee beleidsmatig en technisch zorgvuldig moet worden omgegaan. Alleen het volwaardig meenemen van de bodem in het operationele beheer van bodemenergie-systemen kan het behoud van deze accu functie waarborgen. De eerste resultaten van een raamwerk waarin bodemenergiesystemen informatie uitwisselen en zelf het gebruik van de ondergrond regelen zijn veel belovend en wordt aan de hand van case studies en verdere detaillering van de modellen en controller uitgewerkt.